Everyone in Karachi is running; running on a prayer.

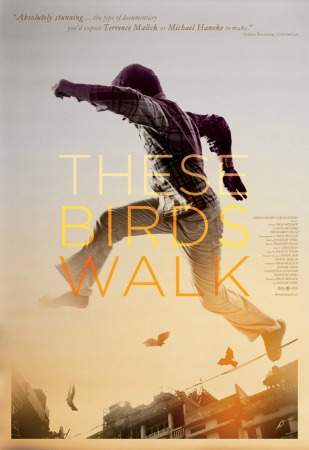

“These Birds Walk” is a hopeful ode to the resilience of the people of Karachi and one of its home-grown heroes, Abdul Sattar Edhi.

Directed by the diaspora kids Bassam Tariq and Omar Mullick, the documentary film focuses on a home for runaway boys in Karachi run by the Edhi Foundation. They had originally set out for Karachi, Pakistan to make a film about Edhi himself, but once there, they were not able to. Edhi Sahab, as he is affectionately known, was not interested in a film about himself and said to them, ”I am an ordinary man, go look for me in ordinary people, you will find me.”

So they did.

In case you don’t know, Abdul Sattar Edhi is a humanitarian legend without an agenda, not even an ‘Islamic agenda’, and on the streets of Pakistan he commands respect. Not through political power, but through the services he and his wife provide to the poorest of the population; services that neither government nor non-government entities have provided for the past 60 years. He can walk the street and do the work that he is doing without being pushed or pulled into controversy. People trust him on the streets, and he provides critical services from the cradle to the grave. His orphanages have drop-off boxes for babies, and his ambulances recover the bodies of the dead. The Edhi Foundation is organic and fluid, and in the film is a reflection of the uniquely Pakistani way that it adapts in order to serve.

Edhi’s work is happening, everyday, with every ambulance that leaves the Foundation’s 330 centers around the country, picking up the dead who can’t afford funerals, or dropping off runaways to their homes, or feeding the hungry in Edhi Homes. This film is not a cry for pity, but a privileged glimpse into what’s happening from a position of empathy; Pakistanis taking care of their own. “They are doing just fine without us having made a film about them,” said Bassam Tariq.

The film is a refreshing departure from most documentaries: no talking heads, no stats presented. The cinematography is simple, and it flows with the energy of Edhi’s work- unscripted, unassuming, running in wake of an ongoing story.

Mullick captures Karachi’s essence from the first shot, desperate and free. He shows us the city as it is seldom seen; stunningly framing the section of Clifton Beach where the camels go home after the moneyed and the tourists have ridden them, panning the crowded streets with a dead body inside an Edhi car, cutting into the fringes of a megalopolis where the streets have no names, or power, or gas.

“These Birds Walk” is made with the intimacy of an old friend, and through its closeness, humanizes the lives and energies of boys who run away from home and young men who bring them to a safe space. It is made with an aching love for the country where these people live.

The film captures the universality of boyhood, even in poverty and darkness; and the longing for home, despite dysfunctional families. Tariq and Mullick say that the children are not as photographically aware as children here, so they forgot about the camera as they filmed, giving the audience an honest look at their days in the simple, clean home.

Mullick says that it is a generational picture: there is a child, a young man and an aging humanitarian.

We meet Omar, a young boy living in the shelter who consoles other boys by night and picks fights with them in the morning. The boys talk about God and family -a lot. Omar placates his friend, Shehr by reminding him that Allah loves him more than his mother. Islam is kneaded in the souls of Pakistanis and the elitist media does Pakistan no favors by misrepresenting this, notes Mullick.

We later find out that Shehr ran away from hifdh school and his family is searching for him. The children are not forced to go home from the shelter. They don’t have to leave, even if their parents come to look for them.

Shedding his day-time bravado, Omar oscillates between fear and hope as he tries to sleep on the floor of the shelter. Wondering whether he should kill himself, he prays for his family in a haunting scene in candlelight,”Dear Allah tell me what to do.”

Asad came to Edhi from the streets, abandoned by his parents. He is an ambulance driver for the foundation and a Pakistani version of the child protective services. With him, the filmmakers travel deep into the city, picking up overdosed dead bodies and returning children to their homes. Like an Urdu-speaking cowboy, he swaggers into Pashtun territory. “You don’t a tell Pathan that if he doesn't want his kid, that we will take him,” says Tariq, “especially if you are a Muhajir (migrant from India). Asad is a hero.”

Tariq is referring to the scene when Asad- a Muhajir- is returning Rafiullah, a runaway boy from a large, very poor Pathan family, and tells his uncle not to beat him again in front of the entire neighborhood. The two ethnic communities often clash and these little nuances were so subtle that someone who doesn't know the Pakistani political terrain would surely miss them.

Just as desperate as the young boys he rescues, Asad fills his pain by cleaning up the violent street.

The film also shows a respect for gender and women’s spaces in Pakistan. There are girls’ homes as well, but they are protected and inaccessible to men. “We would both die a slow personal death if we- for a minute- thought that we could see five minutes of the female experience and we could then make a statement about it,” says Mullick.

Despite the minor appearances of women in the film, they make some of the most powerful moments- when the hafiz is returned to his family and his grandmother welcomes him home with tears and prayers for the Edhi folks. The women who serve lunch to the boys and make sure the place is squeaky clean, and then the strong, abrasive appearance of Omar’s mother in the finale. The ending unfolds in such a way that its hard to believe that this is a documentary; and easy to forget that Mullick and Tariq and their cameras are on the same emotional ride that we are.

I ask Tariq and Mullick if they felt this would have been a different movie had they gotten permission to film Edhi Sahab from day one. Tariq thinks the fluid cinematic quality wouldn’t be there as Edhi is in his eighties and no longer as mobile. He is still a very active part of the organization however, and at one point as Edhi was bathing some orphans he comes alive and asks, “Who will bathe them?”

The real question is who will bathe them after Edhi passes on. Mullick and Tariq hope the film makes you want to go do something; to stop running and take whatever you have and answer your own deepest questions.

Comments powered by CComment